Garden passion at Sissinghurst Castle

For garden lovers traveling to England, a visit to Sissinghurst Castle is certainly a must. The white garden is world-famous, and the collection of old rose varieties is legendary. The passion of the two creators for gardening can still be felt today, making Sissinghurst one of the most beautiful gardens in the world.

Sissinghurst Castle Gardens

"Was overwhelmed with love," Vita Sackville-West wrote in her diary after seeing the dilapidated Elizabethan castle ruins for the first time on a rainy day in April 1930. There was no proper residential building, just a tall rectangular tower flanked by two octagonal turrets and two dilapidated cottages scattered around the grounds, remains of Tudor walls, and a gatehouse with stables.

The imagination of the writer and her husband, diplomat and journalist Harold Nicolson, was ignited. Three weeks later, they purchased the property with approximately 3 hectares of farmland. For the next 30 years, Sissinghurst consumed their lives. Until Vita's death in 1962, the couple transformed a wilderness of nettles and piles of rubble into one of the most famous gardens—for many, the most beautiful garden of the 20th century.

Along with Hidcote Manor, Sissinghurst serves as a model for the architectural garden, also known as the English garden of the 20th century. This style of garden, known in England as a formal garden, developed at the beginning of the last century and has remained popular and dominant in Great Britain and on the continent to this day.

While Harold Nicolson, sensible and classically oriented, designed the basic framework of the garden, the poetic and romantic Vita Sackville-West took over the planting.

Harold integrated the residential buildings scattered across the property into the garden. Brick walls, stairs, and paths complete his architectural framework. The floor plan corresponds to the buildings and extends daily life into the garden.

To get from the kitchen and dining room in the Priest's House to the study in the tower or to the bedrooms in South Cottage, Vita, Harold and their two sons Nigel and Ben walked across their garden in all weathers.

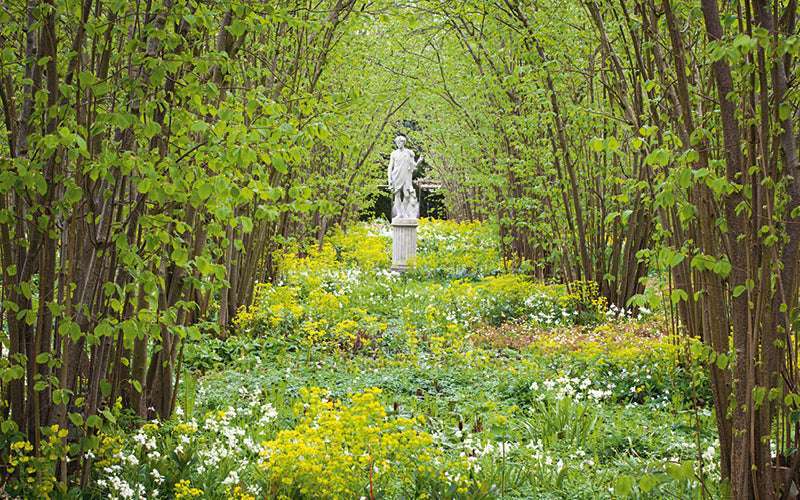

Like the rooms of a house, Harold Nicolson divided the area into different garden spaces. Separated by walls and strictly trimmed, dark green yew hedges, the style and character, as well as the colors, of each room could be distinct. He planned long lines of sight and path from north to south and west to east, like the central corridors of a house. Small geometric gardens open up from the paths as an intimate surprise. The endpoints of the paths, marked by a "Lutyens bench" or "the statue of Dionysus with sentinel poplars," are focal points that arouse curiosity and guide the viewer through the garden.

As a contrast to the strict architectural layout, Vita Sackville-West filled the garden chambers with a vibrant array of plants. Vita's love of opulence, generosity, and aesthetics is also expressed in her garden philosophy. She abhorred anything stingy or shabby. The poet loved the old garden plants from Shakespeare's works and was inspired by the design ideas of William Robinson and Gertrude Jekyll, as well as by travels to Italy and Persia.

Climbing roses, honeysuckle (Lonicera), figs (Ficus carica) and purple vine (Vitis vinifera 'Purpurea') were to cover the morbid, old-pink brick walls with tendrils of flowers and leaves, a sea of lush flowering perennials was to spring from the beds and fragrant herbs in the Herb Garden were to tell stories of times gone by.

Vita designed the ten garden spaces like a play, evoking the seasons with successive flowering peaks. Vita further developed Jekyll's idea of "painting" perennial beds with colors like an artist with the planting of the legendary White Garden, a monochrome summer garden entirely in white.

Old roses held a thrilling fascination for the poet. At the beginning of the last century, these once-blooming shrubs were almost forgotten. In her columns in the Observer, Vita wrote passionately about moss roses, centifolias, remontant, and gallica roses, and caused a sensation in the gardening world with her rose collection in her old walled kitchen garden.

"Anyone who has once fallen under the spell of old roses will never be able to embrace new ones (...). As with friends, one learns to overlook their faults and appreciate their virtues." All the poems about roses one has read and portraits one has admired in paintings come back to mind at the sight of 'William Lobb,' 'Baron Girod de l'Ain,' 'Cardinal de Richelieu,' or the velvet rose Rosa gallica 'Tuscany.' In purple with a velvety sheen, in silky pink tones, and with a stunning fragrance, old roses evoke emotions. "Velvet rose. What a combination of words! (...). It teaches one something to gaze long and intently into a rose blossom, especially a rose like 'Tuscany,' which opens flat, revealing the tremulous and dusty gold of its central perfection."

Sissinghurst has become a myth. While visitors admire Hidcote Manor Garden, planned with all the finesse of the Arts and Crafts movement, Sissinghurst captures their hearts, despite the comparatively simple garden concept and Vita and Harold's low regard for building materials. Yet Sissinghurst is a private garden, an intimate place of retreat, as Harold emphasized in 1963: "(...) a garden should be for the enjoyment of its owner, not for display (...)."

In her novels and poems, such as "The Garden," Vita writes about her deep relationship with the garden. For her, gardening was an endless experiment. She loved England, and especially Kent, and grew up in Knole, the largest Elizabethan castle. She wanted her garden to be English, to blend seamlessly into the idyllic Kentish landscape, the Garden of England.

Vita loved living and gardening in her country garden. This still closely reflects the wishes of many garden lovers today. After Harold's death in 1967, Nigel Nicolson handed Sissinghurst over to the National Trust. Since then, the management, together with the Head Gardeners, has strived to preserve the intimate, private atmosphere of the garden—which is not easy with 145,000 visitors per year (2012).

Nevertheless, Sissinghurst is a must-see for garden and history buffs. Many ideas still recommended in gardening magazines and books on garden design were implemented almost 100 years ago by Vita, Harold, and their head gardeners Pamela Schwerdt and Sibylle Kreutzberger. The garden has now reached its peak. The goal of the head gardeners is to maintain Sissinghurst at a high horticultural standard as a source of inspiration for keen gardeners.

The recommended entry point to the garden is the climb up the tower. Vita's study appears as if she had just left it, with fresh flowers and a photograph of her beloved friend Virginia Woolf on the desk. The view from the roof terrace is breathtaking. Here, not only does Harold's architectural garden concept and Vita's abundance of plants become tangible from a bird's eye view, but it also makes it clear that Sissinghurst is more than just the garden.

The ruins of the Elizabethan house with its gardens, the adjacent farmhouse, and the oast houses, the traditional hop kiln houses with their white conical lace roofs, are set amidst the green Weald landscape of woods, streams, and farmland. Walking paths wind past two small lakes into the deciduous forest where Vita's dogs are buried. The view extends far over the fertile fields and meadows with old gnarled oaks into the park and hedge landscape, into the Garden of England. All the impressions, images, and stories about the personalities of the designers touch many people and make Sissinghurst a unique place.

← vorheriger Post: Piet Oudolf's Perennial Paradise

The content of this article is from the book:

Anja Birne

The most beautiful garden tours in England

Visiting romantic gardens with the best insider tips

Price: 39.95 €

ISBN: 978-3-7667-2509-7

Callwey Publishing

The book "The Most Beautiful Garden Tours in England" was developed by garden journalist Anja Birne based on her experiences on private and professional garden trips. It features 12 major tours, stretching from Kent in the east to Cornwall in the west, to the Cotswolds and the green metropolis of London.